My Own Back Pages

Dylan was my gateway drug into the previous two generations of music, arts, and invention: providence, songs, chords, ambitious poetry and transcendent dreams.

I am an unapologetic Dylan fan. In 1979, I borrowed Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits and Street Legal albums from an older church friend. I was fifteen and curious about the singing poet. I found myself playing the albums incessantly. I was already dabbling in hackneyed attempts at poetry and science fiction stories for the school magazine. Dylan showed me what actual poetical songwriting could be like with a vocal range not beyond my own.

I borrowed a school guitar for the summer holidays and made an out-of-tune racket. I learned all the lyrics for several of his albums, particularly Blonde On Blonde and Highway 61 Revisited, which started with his seminal track "Just Like a Rolling Stone." A year later, I got Grade One in CSE Music after I wrote essays on Dylan and Tchaikovsky, respectively, and composed and played a piano tune influenced by Mussorgsky.

I read so much and listened to every conceivable selection of music, partly because of where my interest in Dylan led me: the Southern blues, English folk, and rock jostled in my head alongside the new wave music of the day. I began to explore the technical side of song construction, storytelling, and guitar chord sequences. He was one of my gateway drugs into the previous two generations’ music, arts, and invention.

The new wave post-punk years were as fruitful and exciting as anything in popular music. At the time, my own generation's view of Dylan involved either an unselfconscious reenactment of hippiedom that clung to Dylan and others from the dwindling folk music scene; or a deeply disinterested, bordering on hostility to folk, the sixties, glam rock or any of that old shit. For many of my schoolmates, Dylan couldn't sing.

He belonged with ballet, opera, all jazz music, and southern blues in the old and boring section at the library. Irrelevant, dull, and, did I say, old? The Rolling Stones, the Beatles, etc., were also under attack when the Tubeway Army went to number one with “Are Friends Electric?” Even the electric guitar and drum kits were up for grabs. My mates were into Ska, Reggae, punk, the Banshees, Chic, ELO, Madness, and the Slits. Meanwhile, my family elders still liked Abba and Slim Whitman, Carly Simon, Johnny Nash, or anything on the Top of the Pops without swearing. But definitely no wheezing harmonica’s

The odd teacher, Church grown-up, or later anyone with an extensive record collection who fed my addiction was occasionally aware that they may have unleashed a monster. I brought my copies of Dylan’s albums and started to study everything about Dylan. Sure, I raided the local library and taped a kaleidoscope of music and performers that interested me. I liked the Incredible String band through to David Byrne and Leonard Cohen alongside those at the top of the pop charts, such as Blancmange’s “Living On the Ceiling”.

But between the disdain of many friends, the shallow reverence of the Woodstock wannabes, and the frank exasperation of those who had grown up with his music and felt I was overdoing it a bit, I developed a really helpful thick skin. I could like anything if it appealed to me; almost as soon as I started to listen to Dylan, he, of course, went and got born-again religion, as if to make things even more black and white.

The signs had been there in Street-Legal. His Christian “phase” produced three overtly religious albums bookended with two more subtle works; perhaps five albums in total —Street-Legal, Slow Train Coming, Saved, Shot of Love, and Infidels—his nonplussed audience was often embarrassed, particularly by the gospel preaching at his concerts. A teacher who had encouraged my interest and lent me New Morning and Blood on the Tracks gave me his copy of Slow Train Coming, which he described as crap, with the bitterness of a jilted lover. But even as I was slowly losing my religion on the altar of teenage lust and theodicy, I always got Dylan’s albums.

imagine a world without "New Pony", "Baby, Stop Crying", "Is Your Love in Vain?"., “Señor (Tales of Yankee Power)" and the stunning "Where Are You Tonight? (Journey Through Dark Heat)", all from Street Legal; “Gotta Serve Somebody.,” “I Believe in You" and "Slow Train" from Slow Train Coming; "Covenant Woman" and “Pressing on” from Saved; "Property of Jesus", "Dead Man, Dead Man", and the outstanding "In the Summertime" from Shot Of Love; "Jokerman", "Sweetheart Like You", "Union Sundown" from Infidels.

These days, I seldom meet anyone who knows more about his work than I do. However, I have generally had less time for music in the last decades, fatherhood, work, home chores, and church all take up valuable time. I still see his worst album as the execrable Down in the Grove, not Self Portrait. If I talk to someone who claims to be a “Dylan fan” and they mention, say, the inventiveness of three-dimensional storytelling of Blood on the Tracks and yet overlook Desire and, in particular, Planet Waves, it diminishes their opinion in my eyes. I am clearly a bit of a Dylan snob.

Planet Waves, subtitle Cast-iron Songs & Torch Ballads, is referenced in one of my still-to-be-completed songs and is a masterpiece of an album in its own right. The arrangement for Never Say Goodbye is one of the best pieces of work with The Band. I saw Dylan in 1984 at Wembley Stadium and was not disappointed. In a recently available interview he is generous, friendly, unguarded and engaging. His point, 25:00 minutes in, about albums either having or not having “histories”, is fascinating and goes someway towards explaining the oversight of Planet Waves, Shot of Love, New Morning, etc.

Fast-forward nearly forty years to the album The Tempest, and you have the impressive “Early Roman Kings,” which came out in 2012. The last couple of decades have seen the issuing of a fine catalogue of “bootleg tapes” of all phases of Dylan's career. And the oddly enjoyable album—I’ve just brought Shadow Kingdom, which contains bravado cabaret-like performances of his classics.

But Dylan is generally as enigmatic and evasive as he has ever been. Most of what he says is tongue-in-cheek, misdirection, and obfuscation. Eventually, I realised I would never understand who he was as a person. Neither do I think my takes on his songs involve tapping into some Protestant sola scriptura inherency. By contrast, it is all a way of looking, riffing, opinionated and taste: bad and good.

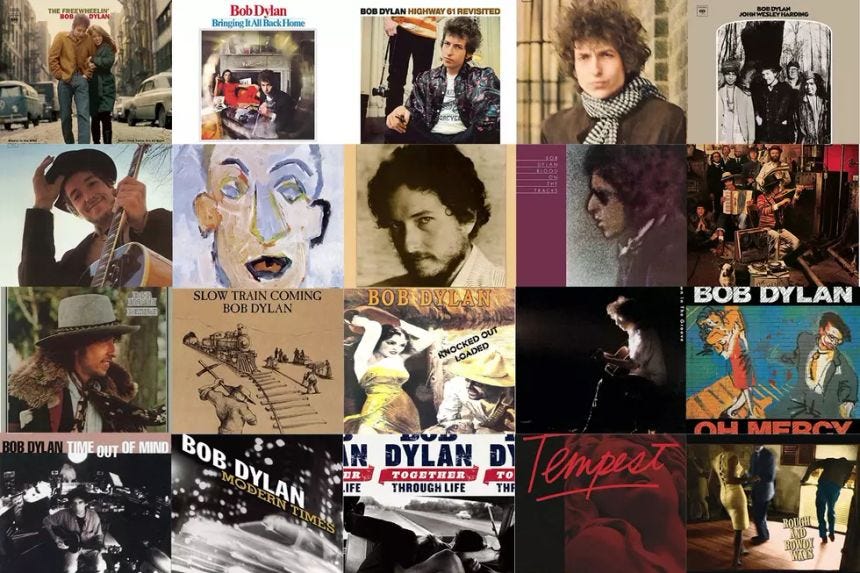

There is a debate whether Bringing It All Back Home, Highway 61 Revisited, or Blonde on Blonde is the quintessential work of genius for the post-folk period of Dylan's career. This and the preceding folk period Bob Dylan, The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan, The Times They Are a-Changin', and Another Side of Bob Dylan - are used to judge his subsequent work. As albums go, I have to select Highway 61 Revisited. “Just Like Tom Thumb's Blues” is a lifelong favourite.

“When you're lost in the rain in Juarez

When it's Easter time too

And your gravity fails

And negativity don't pull you through

Don't put on any airs

When you're down on Rue Morgue Avenue

They got some hungry women there

And they really make a mess outta you…”

Bringing It All Back Home has so many classic records, both electric and, on side two of the album, four acoustic songs “Mr Tambourine Man," “Gates of Eden” “It's Alright, Ma (I'm Only Bleeding)! and “It's All Over Now, Baby Blue" which permanently rewrote the parameters of the folk song genre and concluded a journey he had started with “A Hard Rain’s Gonna Fall” three years earlier—surreal, elongated, poetic landscapes - the existential muse Prospero-like that we also hear on Highway 61 Revisited’s “Desolation Row”.

All modern folk music has operated within the shadows cast by these works. Joni Mitchell, Paul Simon, and many others have produced great works, but all that follows is defined by comparison and association even if subsequent generations are unaware of this.

Aside from the Incredible String Band’s genius-level 1968 The Hangman’s Beautiful Daughter or Roy Harper’s seminal early seventies albums Flat Baroque and Berserk, Stormcock, Lifemask, Valentine, and HQ, in particular, the elusive “Watching to Many Movies” nothing has come close to pushing the envelope or adding to Dylan's “last words” on what can be done with folk-rock poetic storytelling, including the maestro himself.

But, I have picked a song from his album Blonde on Blonde. I could have picked the brilliant “Visions of Johanna”, the album version or the live performances, which can now be enjoyed on YouTube. I could have picked the amazing, long, surreal poem “Stuck Inside of Mobile with the Memphis Blues Again”. (As an aside, I once attended a poetry recital by Sophie Hannah where she recited a poem in which each verse ended with a reference to the Edinburgh Woollen Mill; I pointed out the similarity with “Stuck Inside of Mobile …” but she was none the wiser). Using one repeated line to ground a collection of verses is not Dylan’s invention, of course, but he does use the technique well. Take the masterful “Slow Train Coming” as another example.

But “One of Us Must Know (Sooner or Later)” was one of the songs that intrigued and mesmerised me in my mid-teens. I heard it first on Bob Dylan's Greatest Hits. Many of Dylan's songs work because they fire the listener’s imagination at the exact point where his lyrics are the most vague, conjuring up juxtapositions or surreal images with deleted context. Bowie used to do the same: write lyrics and then chop up sentences and reassemble them so that it is not what the song says but what it evokes that we respond to.

What I did not have back in 1979 and do have now is access to the bulk of that day on January 25, 1966, when Dylan turned up at the recording studio with a sketchy series of lyrics and a broadly agreed piece of music and set about sharing them with a mostly bemused group of studio musicians before launching into several recorded versions and potential arrangements with minimal direction but on a quest of an elusive “tempo.”

One of us Must Know, like many of the seminal tracks on the album, starts with a jumble of competing, resolving instrumentation, Dylan's own wall-of-sound quest for a circus band ensemble that he claims he has seldom matched since Highway 61 Revisited. Each ascending verse of music crashes like a wave over the chorus - drums, piano and organ are orchestrated by harmonica or vice versa. Dylan sings in a low register with all the emphasis coming from the dramatic, assertive, often pleading phrasing.

Everything is ambiguous. The song is probably addressed to an ex-girlfriend following a breakup, and we assume Dylan is the former partner. Events are referred to as snapshots. At times, there are apologies and bargaining, but above all else, it's observational and intimate. We hear the woman through the perspective and recollections of the man and snatches of their sometimes tempestuous relationship. It's both lacking in emotional intelligence and yet saturated with it.

What's most noticeable is how the lyrics dramatically change during the sequence of recorded versions—some of which negate entirely the claimed intentions behind the final lyrics that many Dylanologists have dined out on. Back in the late seventies or early eighties, the word misogyny had a specific meaning: a very rare hatred of women, bordering on the Maquis DeSade sadomasochism. Even “sexism” was a newly minted word focused on whether to use the term Chairman or Chairwoman, or Actor and Actress, whether to open doors for or seat a woman at a table. The term male chauvinist pig was only just receding but applied to men who saw women as intrinsically inferior or that they should know their place in the home, raising the babies, etc.

After reading the next sentence, you might need to sit down: back then, boys and girls, women and men did not always agree. I know shocking! They often misunderstood each other, misread signals, talked past each other, and overreacted. The opportunities for interaction between the sexes at such early post-puberty ages were now more possible with unparalleled freedoms that previously were far more regulated. A teenage boy has to learn how to be a man, and part of this involves making heads or tails of girls and trying not to sound like a pillock when approaching them. A few people labelled it, but it was what it was.

Some reviewers tried to brand “Sooner or Later” and do to this day. Dylan is “manipulative”, “misogynistic”, and “operating with bad faith”. The opposite is assumed for the unknown woman even after he claims, presumably metaphorically or dramatically, that she had “clawed out my eyes”. But as a 15-year-old, it all made sense to me. Talking to girls in 1979 was a minefield, but i perceived until one took pity on me; not much would change on that front.

Here are the final lyrics when the song was released as a single:

One of Us Must Know (Sooner or Later)

“I didn't mean to treat you so bad

You shouldn't take it so personal

I didn't mean to make you so sad

You just happened to be there, that's all

When I saw you say goodbye to your friend and smile

I thought that it was well understood

That you'd be comin' back in a little while

I didn't know that you were sayin' goodbye for good

[Chorus]

But, sooner or later, one of us must know

That you just did what you're supposed to do

Sooner or later, one of us must know

That I really did try to get close to you

I couldn't see what you could show me

Your scarf had kept your mouth well hid

I couldn't see how you could know me

But you said you knew me and I believed you did

When you whispered in my ear

And asked me if I was leavin' with you or her

I didn't realize just what I did hear

I didn't realize how young you wereBut, sooner or later, one of us must know

That you just did what you're supposed to do

Sooner or later, one of us must know

That I really did try to get close to you

And I couldn't see when it started snowin'

Your voice was all that I heard

I couldn't see where we were goin'

But you said you knew and I took your word

And then you told me later, as I apologized

That you were just kiddin' me, you weren't really from the farm

And I told you, as you clawed out my eyes

That I never really meant to do you any harm

But, sooner or later, one of us must know

That you just did what you're supposed to do

Sooner or later, one of us must know

That I really did try to get close to you.”

I see Sooner or Later is a song with all kinds of nuance, because I took Dylan at face value. When he says “…you just happened to be there, that's all.” I assume it means she witnessed something that he wished she had not. I do not see the line as an existential putdown of womankind. Even at 15, I thought there was something about the pairing of:

“I couldn't see what you could show me

Your scarf had kept your mouth well hid… "

The juxtaposing as well as the phrasing of the second line both conjured up images and held a finesse.

“Lay down your weary tune, lay down

Lay down the song you strum

And rest your-self ‘neath the strength of strings

No voice can hope to hum…”Lay Down Your Weary Tune

I still have my poetry journals from 1979. I can see my early attempts to write, emulate, and understand language and lyricism, creating and borrowing from Dylan and many others. But it was not until 1982 that I finally wrote songs that pleased me.

A key thing I learnt from Dylan was phrasing—how to space a lyric - which syllables to emphasise, which to hurry over. Then, I learned how to tell a story, move forward and backwards in time, leave out words and text while retaining meaning, and use dialogue and evocative imagery to punctuate it all with rhythm guitar and picking. It’s in all other great writers, of course.

I first heard “Lay Down Your Weary Tune” on a genuine bootleg album. But it inspired me even through a period of avowed atheism, I was always looking to rest myself ‘neath the strength of strings.